It’s Time to Acknowledge the Invisible Caregivers

Table of Contents

Originally published on The Society for Participatory Medicine Blog

What do I do?

I received an uncharacteristically anxious text from my friend Aileen: “I am having an emergency with my Mom. Please call ASAP.” When I last talked to Aileen, her mother’s dementia had gradually worsened. A little more confusion, a stovetop left burning after cooking a meal. Now, her mother was significantly more agitated and paranoid—pacing the halls, hearing music convinced her family was plotting to kill her. She wasn’t sleeping, so Aileen and her father were on duty 24/7. It had become unsustainable.

Aileen didn’t know what to do.

She wanted to protect her mother and feared triggering her mother’s panic by entrusting her to unfamiliar medical staff. But I could see the writing on the wall—If they didn’t get professional help, they would fall apart. I finally convinced Aileen to go to take her mother to the ER; clarifying that asking for help wasn’t a sign of weakness but a sign of strength.

Support patients

Like most physicians, I never learned about the issue of family caregiver burden in my medical training. I hadn’t noticed caregivers in the hospital halls because I was trained to focus on the patient.

But if the support structure around the patient is crumbling, the patient will, too. I became aware of this issue only after making a film about a friend who went home from hospice to die. But during the film's editing process, I realized that her husband’s story was more urgent. I had thought of him as a secondary character, someone to open the door for the hospice nurse. But his continued deterioration throughout the film was impossible to ignore.

Family caregivers suffer

My friend Aileen is not unique. She is one of 53 million people caring for family members at home—one in 5 Americans, 20% of us and the number is rising fast. As families shrink and disperse and divorce and debt rates rise, we are entering the perfect storm. And the stress of the pandemic has punched an extra hole in our already leaky boat.

Most caregivers like Aileen don’t have many other family members around to take shifts and help with the stress and work. Caregivers become progressively exhausted, financially debilitated, isolated, and overwhelmed. Their health suffers, too.

3 days of respite

When Aileen checked her mother into the hospital, she got three days of rest and her first whole night’s sleep in months. Her mother returned calmer and was able to settle back home. But now they were anxious. It wasn’t a matter of if her mother would decompensate (decline) but when. The situation felt like a ticking time bomb.

So what can healthcare providers do to help caregivers like Aileen?

How to change the system?

Let’s start by identifying the caregivers associated with our patients. Caregivers are everywhere; it’s just a matter of looking for them. Many patients don’t realize that their wife or daughter is their caregiver, and many caregivers don’t realize that they are more than just a wife or daughter.

1) Ask the patient:

Who goes to the pharmacy for you? Who drove you to your appointment today? And as a physician, we need to remember that your patients might be caregivers too.

2) Acknowledge their work:

Once you’ve identified a caregiver, acknowledge their work—the love, sacrifice, and loyalty it entails. Many caregivers have told me that simply having their physicians or nurses realize these issues makes them feel empowered and less alone.

3) Be sensitive to caregiver mindset:

Be sensitive to the fact that caregivers often experience guilt, shame, and inadequacy around their role. As such, they are unlikely to ask for help. And even if they are open to getting help, they are often too overwhelmed to utilize service.

4) Support caregivers:

As healthcare providers, it’s our job to lean in and initiate support, not to wait until caregivers are worn out and depleted.

5) Clarify patient medical goals:

Identification of a caregiver is an excellent time to clarify the patient’s medical goals and encourage the completion of a POLST form if appropriate. This ensures goal-concordant care for the patient and help support the caregiver, who will likely be the one tasked with making difficult decisions when the patient’s condition worsens. When I asked Aileen what treatments her mother would prefer in the event of major organ failure, she was adamant that her mother would not wish to be kept alive on machines and would like care focused on comfort. Not only did Aileen’s mother not have a POLST form, her physician had never brought it up.

6) Connect caregivers to resources:

Finally, after identifying caregivers and acknowledging their experience, we must connect them to helpful resources—professional and personal.

Hospitals should be well-connected with the resources in their local community and have the personnel, often social workers, who can connect patients with resources like hospice, respite, support groups, educational programming, and other programs and benefits that can aid them in this journey.

Family caregiver burden is a rising public health crisis that will eventually affect almost all of us. As clinicians, we are in a prime position to offer help to this critical workforce. It’s time for us to acknowledge the invisible caregivers among us.

“My biggest goal is to raise awareness to a variety of audiences about what it really means to be a caregiver,” Zitter said.

It’s not unusual for the health of caregivers to become precarious. Studies support the fact that people who are the primary family caregiver for loved ones with Alzheimer’s have an increased risk for developing dementia. As many as 30% of those caregivers, according to Zitter, pre-decease the patient.

And for caregivers in general, their emotional and physical health can suffer resulting in anxiety, depression, cardiovascular problems and more.

“The average length of time that caregivers are taking care of a loved one is four-and-a-half years."

It is republished with permission of the copyright.

Partners in this Article

Everplans

Everplans helps you organize, store, and securely share all of your most important information. From your home, to your documents, to your personal decisions.

Care.com

Care.com connects you to vetted professionals to help you manage the daily demands of child care, senior care, pet care, and housekeeping.

Happy Healthy Caregiver

Certified Caregiving Consultant and founder of HappyHealthyCaregiver.com, Elizabeth Miller offers family caregivers one 30-minute complimentary coaching session.

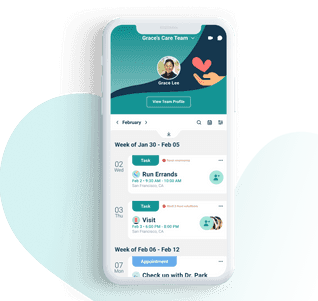

Build Your Family Care Team Today!

It’s no secret that taking care of elderly family members can be a challenging task. Not only do you have to worry about their physical and emotional well-being, but you also have to manage your busy life simultaneously.

If you’re a family caregiver, CircleOf is the app for you. It allows you to organize and collaborate with family and friends, maintain regular communication so everyone is on the same page. Download CircleOf today to build your circle of care.